- Home

- John Young

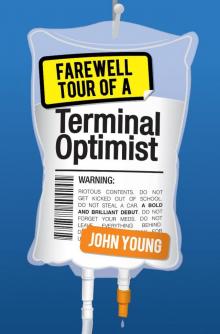

Farewell Tour of a Terminal Optimist

Farewell Tour of a Terminal Optimist Read online

For your daily love and inspiration

Laura, Nina, Verity and Isla

Contents

Title Page

Dedication

Chapter 1: C’est La Vie

Chapter 2: A Good Man

Chapter 3: Fantasies of Love and Hate

Chapter 4: Needlework

Chapter 5: All About Me

Chapter 6: Underdogs

Chapter 7: Common Denominator

Chapter 8: Kids Go Free

Chapter 9: Soapy

Chapter 10: Two Ducks

Chapter 11: Gumbo

Chapter 12: Nine Years

Chapter 13: Escape From Pizzatraz

Chapter 14: Campervan

Chapter 15: It’s a Bit Slippy

Chapter 16: The Broxden Campers

Chapter 17: Nadie Deja Este Mundo Vivo

Chapter 18: Crash

Chapter 19: Robin Hoods

Chapter 20: Nowhere to Run

Chapter 21: Our House

Chapter 22: I Need You Around

Chapter 23: The Last Night

Chapter 24: Nightclubbing

Chapter 25: Old Macdonald

Chapter 26: Don’t Go

Chapter 27: Parents!

Chapter 28: Compassionate Grounds

Chapter 29: We All Have to Die Sometime

Chapter 30: Suiting Up

Chapter 31: Your Own Sins

Chapter 32: The Meaning of Silence

Chapter 33: Sins of the Father

Chapter 34: More Common Denominators

Chapter 35: Room 9

An Interview with John Young

Connor and Skeates’s Journey

Listen on Spotify

Acknowledgements

Copyright

Chapter 1

C’est La Vie

By the time boys reach the age of fifteen, they want to look like chiselled gods and not… well, not like me. Thankfully, every fifteen year old has fantasy superpowers, so although I might look like Gollum on the outside, inwardly I can turn myself into whoever I want. Right now, due to my urgent need for speed, I’m thinking Usain Bolt.

Fantasies aren’t supposed to come true, are they? Realised fantasies carry baggage, you can’t get away from that fact. Take this guy Skeates at my school. He thinks it’s funny to kick my right leg from behind – that’s the one with the caliper – so that I fall over and his mates laugh. I do nothing, because I can’t, so he keeps doing it. What do you reckon my fantasy is about Skeates and which rusted, pointed hot things are sticking out of him by the time I am done? My dream would have me in prison, like my dad. Nightmare.

Anyway, back to my need for speed. While Skeates was distracted in the lunch queue, I snuck a dead bird into his lunch. I’m now hovering at the door to watch him take a bite. I left my own plate on the table even though the dinner ladies think failure to clean up after lunch is a crime akin to stabbing the school cat. Skeates is a headcase, so you can appreciate why I haven’t hung around to scrape congealed beans into the slops bucket.

Thing is, I have nothing to lose. I’ve known my fate since I was seven years old. Back then, sitting in Room 9 in the oncology ward of the hospital in Inverness looking at the Where’s Wally pictures plastered over the ceiling and walls, I accepted that I had pain in my swollen stomach, that I limped, that instead of getting better, I would get worse.

My doctor said, between my mum’s snivels, “Mrs Lambert, your son has cancer.”

That was eight years ago. My multiple daily medicines and baldness-inducing chemotherapy have so far kept the Grim Reaper at bay – at least until the next round of tests. I just hope my dad gets out of prison before I snuff it. Dad has been locked up since I was six years old, and to this day I still don’t know why. I haven’t known for so long that for years I even stopped asking the question. It’s not that I stopped caring about him; not a day goes past when Dad doesn’t enter my head. In fact everything I do is because of him. Even this sick little deed with the bird.

I used to daydream about stuff that was never likely to happen: arriving at the school disco with Chloe Moretz, riding a horse, being a spy, having laser eyes like Superman, getting abducted by aliens, winning the 100-metre final, snogging my English teacher, getting top marks in my exams. Now, my fantasies are more down-to-earth. Live a life, find a girlfriend, get back at Skeates. But I’ve kept my most unlikely fantasy of all: see my dad out of prison.

I catch my friend Emma’s look of disgust as Skeates unwittingly stuffs the dead bird into his mouth. She winces as he retches the manky feathers and broken bird bones out onto the table, then he catches my eye. He flings his plate to the floor. He won’t care about the mess, he knows that no one in our school says squat to him, ever. At this point the only thing on his mind is killing me. He leaps from the chair like it’s electrocuted him.

Time to go. Come on, Usain Bolt.

I loosen my caliper, turn and leg it.

The clattering of plates grows slowly dimmer as I move as fast as I can, but I’m thinking it’s unlikely to be fast enough.

Skeates’s manic yells are nearing.

“Tayyytieeeeeee! Tayyytiiiiiiiiiiii, Taytiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiieeieii!”

I hobble like a hound-mauled bunny.

Lippity, lippity, lippity…

“Taaayyyyttiiiiieeeeeeeeeeeee, I am going to KILL YOU!”

Skeates’s taunting voice amplifies in the narrow windowless passage between us. It fills me with fear, which kills the adrenaline and pleasure I enjoyed from dead-birding his lunch.

Clack… clack… clack… clack… clack… clack…

Five pairs of steel heels march in time down the tiled corridor behind me. This old-school signature sound of Skeates’s gang is designed to intimidate before a beating. One of them clangs a radiator with a shinty stick, the lights go out and Skeates fills the darkness with another deranged and spiteful, “Taaaaaaayyyytiiiiieeeeeeeeeeeee!”

I hate that name and he knows I hate it. Short for potato head, ‘taytie’ is a term reserved by the cruel to label the afflicted. Handicapped, disabled, special needs all fit under its umbrella. Simple and discriminatory, ‘He’s just a taytie, you can ignore him’. Except I don’t want to be ignored. I don’t want to be remembered as ‘Hopalong’ or ‘Cancer Kid’. I want to be remembered for something else – anything else. It’s my duty to make sure of that. Hence the dead bird.

“Taytieeeeeeeeeee!” he yells again, closer this time. Much closer. The adrenaline returns – this time in a bad way, inspired not by cocky aggression but by terror.

I see the door that I hope will bring safety. It’s almost time for our maths lesson now and the teacher should be in the classroom planning her sums. Skeates won’t beat me up in front of her. He won’t even go in the classroom – he never goes to maths, or much else, for that matter. Nevertheless, I know that optimism kills the truth, so I don’t sing happy songs quite yet. I continue my limping journey down the corridor hoping to reach the classroom before I get a pasting.

Lippity, lippity, lippity…

My crooked footsteps lip a bit quicker. My leg feels on fire with the pain of the caliper banging against it, rubbing the skin raw, but I won’t give up. If I give up this chase, then I may as well give up everything, and I’ve gone through far too much to do that. The thumping of steel-heeled shoes on ceramic tiles spurs me on.

Clack… clack… clack… clack…

Lippity, lippity, lippity…

I reach the classroom door and I’m tempted to turn and grin. But I’m too late! A hard kick of boot against my leg brace and it gives way, throwing me to the filthy red-tiled floor. A glance inside the room tells me there�

��s no teacher to rescue me either.

I scramble on the slippy surface, like cartoon prey, trying and failing to stand because my leg brace has twisted in the fall, the catch bent by the force of Skeates’s kick. I’m lifted and shoved back down the corridor to the deranged sound of jeers and laughter from Skeates’s pals. I lose my balance and my feet are scooped out from under me, my left ear grabbed and face thumped hard. The pain is awful, the shame worse, yet this isn’t new.

The noise is the worst thing: the shouts, screams.

Suddenly, silence.

For a few moments I feel nothing. I wish I could bottle these moments of nothing, waiting for what’s next. The chemicals in my body don’t know whether to start healing or keep fighting, so they do nothing and nothing is pain-free, silent ecstasy.

The corridor lights come on again. I peek through my slightly parted fingers and I see why they’ve stopped.

“It’s Emo,” says one of them, relaxing his fist.

Oh no, I think. Please no. Not Emma. And my heart sinks into a deep, sickening pit. She shouldn’t see me like this. She shouldn’t be put at risk because of me. I look down the long corridor and see Emma’s hand slowly return to her side after turning on the light. My heart is thumping with fear and shame and I worry about what I can possibly do if they turn their aggression on her.

Skeates holds his grip on me and says, “So what!”

They call her Emo because she hides behind a wall of make-up and pulled-forward hair. The funny thing is she actually likes the nickname. She’s small, tender and shy. Even so, the gang are stumped and don’t know what to do. I hope they feel guilty or embarrassed instead of angry at her for spoiling their fun.

I want to distract them from her, so I kick out at Skeates. He easily avoids contact. I brace for the return thump, exposed and easy to hit. He won’t resist the temptation to cleave me. Yet it doesn’t come. He’s still looking at Emma. She stands nervously at the end of the corridor, balancing the need to help me with the wish not to get thumped. I could cry looking at her, terrified yet standing her ground, despite the fact I don’t deserve her bravery. I brought this upon myself. I wish she would just leave.

“Come on,” one of them says and they slip off.

Skeates lets go of me and, after a moment’s hesitation, swaggers towards Emma. “You come to pick up your monkey, Emo?”

Aw naw, I think. I’ve done this; he’s going to turn on her. I don’t know what to do. Then an idea comes to me, but as usual I haven’t thought it through.

“Come on back, ya goat!” I shout.

Skeates spins and accepts my invitation with glee. He returns to raise his fist one last time.

I’m crapping myself, but laugh anyway. I look him in the eyes with every bit of courage I can muster and shout, “What can you do to me?”

Skeates sums up the cold reality of my situation. “Yeah. That’s right, Taytie. You’re already dead, aren’t you?” He grabs my right ear and whispers into my face. “Taytie, stay down.”

His voice is different, like it’s a request and not a threat. As if he wants me to stop resisting, to give up, then he can walk away with his pride intact.

I kneel on the ground, moving as he twists his arm. My ear stings, and a few little wispy hairs that have grown back since chemo pop out in his grip. I try to smile at him to wind him up. His fist is ready and I brace for impact, which doesn’t come. He knows the score, he can see it in my eyes. The pain of the truth will hurt me more than he ever could with his hands. Even through my grins and jibes, he sees the ghost of the person I really am. He shoves my head hard, turns and leaves me in silence.

I lie on the floor, allowing shame to eclipse the painful bruises. Why shame? As if it’s my fault that I’m bullied? My fault that they beat me? Shame for what they do. Shame for being too weak to defend myself. Shame that Skeates will do the same again to me and to others. Shame that my dad is in prison. Shame that I haven’t seen him for nine years. Shame for being a limping halfwit. Shame for my caliper and cancer. Shame that I need to be rescued by a girl. I try and fail, time and time again, to exorcise that shame with insults and tricks. It never works. The shame–pain retribution cycle spirals ever downwards.

I am shaken from my shame-fest by the approach of soft footsteps. I turn, feeling both thankful and humiliated to see Emma. She saved my arse for sure, knowing full well that Skeates’s gang could easily turn on her. She looks really upset, and I’m sorry for that. Mind you, she always looks morose, with her pale make-up and dark eyeliner.

She helps me to my feet and into the classroom. The teacher still hasn’t arrived, but some classmates have started to trickle in, trying not to look as they pass by me to their seats. I don’t want to look at them either. I sit on a stool and fiddle with my bent leg brace.

“Why do you bait him like that? You know he always beats you, so what’s the point?” There’s anger in Emma’s voice.

Anger at what, I wonder? Anger at Skeates, anger that I never let it go, anger that she’s stuck being friends with me? She takes a tissue from her jacket pocket and dabs my swollen lip. I let her, even though I don’t want to be nursed.

“Did you see his face?” I ask her and laugh like a donkey, all forced, and full of false bravado.

She smiles reluctantly. “That was a disgusting thing to do with that sparrow, Connor. It was really mingin.” She looks over her shoulder and turns to smile at me. “But Skeates is a right mac na galla, so…” she shrugs, her lips turning up at the sides. I smile back. Even though I’m not fluent in Gaelic like her, I know the rude words. “I thought he was going to swallow that bird whole, the way he stuffs in his lunch,” she adds.

“I wish he had,” I say and we both laugh – sincerely this time.

“Anyway,” I say, “I don’t care what he does to me – and if he’s chasing me, he isn’t bullying someone else.”

“Don’t give me that stupid hero stuff,” snaps Emma. “Do you really care about that?”

“I only care for that one moment when I see his face: the anger, frustration and hate, because he’s too glaikit to think of anything that can hurt me. For that single moment I’m happy. I’ve got to him. Nothing else matters.”

“Look at you, Connor.” She holds out her hands towards me in exasperation, taking in my stubbly head, swollen face and deformed leg. “Well, you’re just stupid. Really, really stupid,” she stutters, forcing out the words and shaking her head.

I don’t know what to say.

“Connor, stop this, because I hurt too you know?” she pleads as she examines me like I am a grotesque museum exhibit. “You don’t deserve any of this.”

My whole self shakes with indecision. I’ve known Emma from a distance for ages, but we’ve only started hanging out in the last few months or so. I used to be suspicious of her motives, and although I’m not any more, I still can’t handle someone caring that much about me after so long on my own. My natural instinct grates against sympathy, hating it like an insult even though I know that she means anything but harm. I can’t process the idea that she really cares. I don’t deserve it.

So I shrug and carry on with my bullshit bravado, regretting it even as I say it, “Skeates is right, I’m already dying. What can he do to me? Nothing! C’est la vie!”

Chapter 2

A Good Man

I understood early in life that once adrenaline subsides it’s replaced with regret, and everything looks and feels totally different in the aftermath. When the good old panic-or-punch hormone is pumping I feel alive, invincible, carefree and mischievous, which is a stark contrast to how I feel now, when the pick-me-up of the natural fix subsides. Sadly, however, I have never understood what to do with this knowledge. The fun of the moment always trumps the consequences.

It’s my addiction to that fast kick that keeps me from hiding in the shadows, waiting for the sickness to win. Or waiting for the Skeateses of this world to feel smug at my expense. If I keep fighting, so my theory goes, then

my cancer won’t overtake me, people won’t see me as the sick kid. Instead, they’ll remember me as the stunted lad with enough goose to take on the headers. And for that short period of time I forget the truth.

Looking at my shaking hands now in maths, it is obvious that this whole philosophy is a stupid delusion, a delicate bubble, which must burst at some stage. I’m wiped out after that kicking: bad enough that I’m not embarrassed about having to be nursed by a girl who looks like a bit part in Scooby Doo. Thankfully Emma didn’t try to get me to tell the teacher about what had happened. Even if she had, I don’t squeal.

Common denominators, I think. Focus! I don’t take much in, even though I like common denominators. They make the world feel balanced, equal and fair. Today I’m too busy dabbing my nose with Emo’s hanky to worry about equality of equations. I hope no one notices.

Maths passes without incident. On our way out Emo reminds me that it’s not all over. She nods towards the door.

Through the reinforced glass panel I see that Skeates has come to loiter outside the classroom. My guts tell me that he’s waiting for me, although my mind is trying to persuade my guts otherwise. I look for the teacher, but she’s gone. I stare at Skeates and he grins back, points at me and winks. His signal is clear: my guts were right.

Now the dust has settled I’m exhausted. Fear has replaced the desire for satisfaction that goaded me into carrying out the dead bird stunt. I stare at him with my hate guns, fantasising about hot-poker revenge. Yet I feel too tired and frightened to do anything. I just want to run and hide.

I feel Emma tugging on my arm. “Come on, out the window.”

I look out the door again. Skeates is distracted, chatting to one of his gang. I turn to the window and question its disabled accessibility. We’re on the ground floor, the cupboard shelf bordering the windows is easy enough to clamber onto and the windows open from the bottom. Even if Skeates wasn’t waiting outside the door, climbing out the window would be a laugh.

Farewell Tour of a Terminal Optimist

Farewell Tour of a Terminal Optimist